The idea of new beginnings is something the Resurrection Presbyterian School and Church in the rural community of Old Saasabi is getting accustomed to.

The community was home to a missionary-established Presbyterian church over 100 years ago before it collapsed and moved from Old Saasabi to Oyibi; both in the current Kpone Katamanso district.

Fast forward to 2015 and the leadership of Oyibi Presbyterian Church moved to resurrect the church in Old Saasabi.

A school for the predominantly farming community followed three years later.

Bernard Okoe Bortey, the Resurrection Presbyterian School’s director, recalled that access to affordable education in the community was a major concern for the church at the time.

“Looking at where the community is, people found it difficult with education because they travelled far to nearby communities for schooling,” he said.

The school’s service to its remote community is a testament to how critical low-fee private schools can be.

For better or worse, they are uniquely tailored to the more deprived Ghanaians because of how affordable they are.

This goes some way to explaining what has been described as a surge in low-fee private schools in some of the poorest countries across the globe.

In Ghana, for example, it is estimated that one-third of schools are low-fee private schools.

“If low-fee private schools did not exist today, the number of out of school children that we would have to deal with would be at alarming levels,” observed Stephen Opuni, the Country Director for the IDP Foundation in Ghana.

The IDP Foundation works to support and improve educational infrastructure in private schools serving low-income families.

Its reach remains limited since it only works with schools certified by the Ghana Education Service.

This is not a box the Resurrection Presbyterian School ticks as yet.

Mr. Bortey said, his school is working on securing certification from the National Schools Inspectorate Authority.

For the guardians of pupils at the school, one imagines the absence of any certification falls secondary to the educational needs and affordability.

The nearest government school, where education is free, is almost four kilometres away in New Saasabi.

When the elements conspire against the community, commuting is a challenge.

“Looking at the nature of our roads, when it rains, it is not easy to go out,” said Mr. Bortey.

Aside from the geographic constraints, there are the economic ones that keep children in the small community from accessing education in other private schools.

Mr. Bortey’s school charges between GHS 195 GHS 290 a term, which translates to between $33 and $50, in line with the general standards of low-fee private schools which were once said to cost as little as $1 a week for pupils.

But these fees are still a tall hurdle for this rural community.

“Even how to pay the GHS 195, they have a lot of arrears because they find it difficult to afford.”

With a school population of just 52, stretching from pre-school to lower primary, it is also no surprise Mr. Bortey says school fees are not enough to settle staff.

That’s where the small church attached to the school has offered some reprieve, especially during the 10-month break in academic activity because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“When you even gather the whole fees, it can’t pay [staff] for a term so the church has to come in and support,” Mr. Bortey explained.

It wasn’t much for the staff but “half a loaf is better than none,” he quipped. “During the COVID time, they will come with some rice and oil; something that at least could sustain you or keep you.”

This served as some motivation for the staff of the small school and church to ensure a second resurrection when schools were allowed to reopen in January 2021.

“For a lot of schools, when they reopened, the staff found it difficult to go back because of what they went through [during the pandemic],” Mr. Bortey said.

The strain of the pandemic

This is an observation shared by Enoch Gyetuah, the National Executive Director of the Ghana National Council of Private Schools (GNACOPS), an organisation that works with the Ministry of Education to regulate private education in Ghana.

GNACOPS has over 22,000 private schools in its database; 70 percent of which are low-fee private schools.

His organisation says as of April 2021, over 1,000 private schools collapsed during the coronavirus pandemic.

In some cases, proprietors were happy to give up after the turbulence.

“A person went through this challenge and now, he has washed his completely off this [education] business,” Mr. Gyetuah said.

GNACOPS had been sounding the alarm about the lack of government support for private schools during the coronavirus pandemic and back in January 2021, it said 126 private schools had collapsed.

Even then, Mr. Gyetuah said his organisation watered down the gravity of the situation.

Before the pandemic, a significant number of private schools were already in a fragile financial state and “adding COVID 19 to that worsened the case,” he said. “We didn’t want to sing so sad a song for people to even see the reality on the ground so we had to massage the figures.”

The challenges faced by the schools, primarily financial, are why the IDP foundation considers its support to some low-fee private schools critical.

The foundation, in collaboration with Sinapi Aba Savings and Loans, moved in to support over 100 low-fee private schools in the education ecosystem with grants based on an independent vulnerability rating.

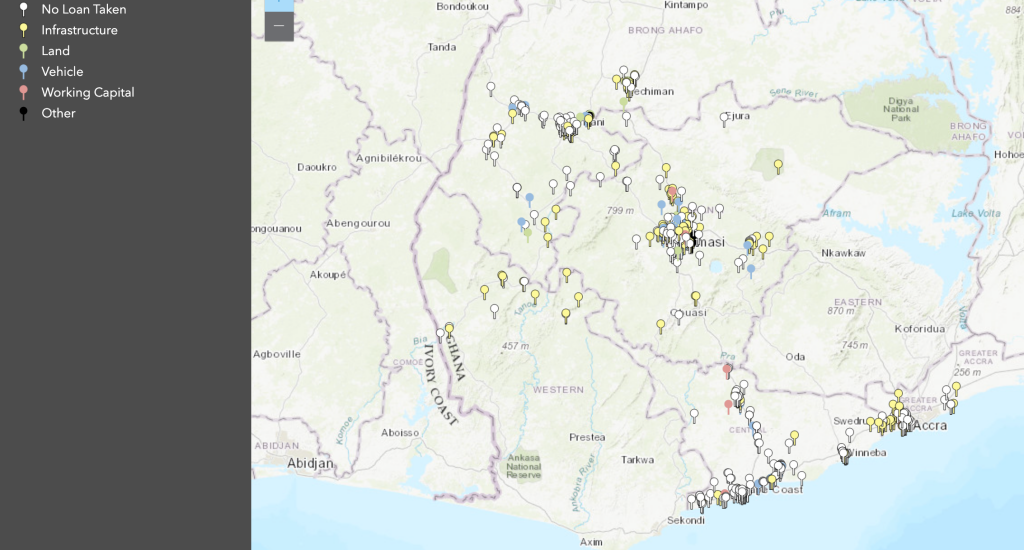

The foundation calls this scheme the Rising Schools Programme and it spans the Greater Accra, Central, Western North, Bono East, Bono, Ahafo, Upper East regions.

A few months after schools were allowed to resume academic activity, Mr. Opuni feels the programme has borne fruit.

“What we know is that a majority of those we have visited so far have reopened and are doing well though a few of them had enrollment dropping a little.”

The foundation noted the 3G’s Royal International School at Tuba-Kasoa as one of the beneficiaries of its support

“I don’t know what would have happened if [IDP] hadn’t come in,” the school’s proprietor, Ruby Coffie, said of the foundation’s support. “The [grant] was used to pay salaries of teachers and to purchase PPE, handwashing materials and teaching aid.”

The reality, however, is that most low-fee, private schools, like the Resurrection Presbyterian School, did not benefit from any serious external help.

“We need support seriously,” stressed Mr. Bortey. Not just for the day-to-day but also possibly expanding the school to give the rural community the best possible education.

The school currently has a small block serving as classrooms for classes one to three. Preschoolers are taught in the church sanctuary which is converted into makeshift classrooms during the week.

On the school grounds, there are signs of materials for a building project that is currently beyond the means of the church and the school.

Right now, all Mr. Bortey can do is make an appeal for support.

“When you look at where the community is and things going on and someone feels like, for this lower-income area they want to come in and help, we will thank God and be grateful for that.”

Infrastructure needs have remained an ever-present challenge for low-fee private schools across the board.

A study by the Results for Development Institute noted that poor infrastructure emerged consistently as the greatest challenge faced by this class of schools.

Mr. Opuni said his organisation’s experiences with low-fee schools they support is testament to this.

“Most of them were in wooden structures but a lot of them have improved a lot in terms of the infrastructure. There has been a lot of progress even though not all of them are out of [out of the woods yet].”

Eyeing the bigger picture

Whilst the Resurrection Presbyterian School hopes to increase enrolment to a more sustainable level, Mr. Bortey is, in the short term, content with the benefits of the low-class sizes.

He links this to the perception of better performances when compared to government schools.

Studies by educational entrepreneurship professor James Tooley in 2007 and 2009 found that students enrolled in low-fee private schools in India, Nigeria, and Ghana generally score higher on standardised tests than students in public institutions.

This is attributed to small class sizes in low-fee private schools and more teacher to pupil contact as compared to public schools.

“The teacher there has enough time for them. When you go to class two, there are only three [pupils],” Mr. Bortey cited as an example.

The perception of low-fee private schools performing better academically, however, does not count for much in the bigger picture as far as Mr. Gyetuah is concerned.

Having worked as an educationist for over a decade, he maintains that “whether private school or government schools, they have not been able to achieve the purpose of education.”

Because Ghana’s has long been anchored on pen and paper tests, “at the end of the day, it doesn’t really bring out whatever education is meant for,” he fears.

Mr. Gyetuah wants Ghana to get to a place where our education does much more than test the mind.

“The purpose of education is to build holistically rounded persons who can apply the knowledge acquired.”

That the outcomes of education need to improve is acknowledged by most stakeholders in the education space.

Mr. Bortey puts on a brave face in this regard saying his school is committed to holistic education.

“It is our duty to bring out that talent for the child to build on it. We are not looking at just academic records.”

The IDP Foundation, whilst emphasising financial literacy and support for schools, also believes improving the standards of education is the endgame.

“The focus for us as a supporter of these [Low-fee private] schools is to now begin to help them improve on the quality of the education they are providing and basically how to improve on the learning outcomes.”

Moving forward, a key sentiment for Mr. Opuni with the endgame in mind is collaboration, given the worsening inequality in education following the coronavirus pandemic.

His words of advise were directed at the government.

“If an entity is already delivering on a goal, what you need to do is probably support it to deliver more,” he said. “This is the time that we need to support those already at the frontlines of education delivery and not to keep them out of the game.”

–

The writer, Delali Adogla-Bessa, is a journalist with citinewsroom.com and Citi FM/TV