For the first time, two leaders of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia have been found guilty of genocide.

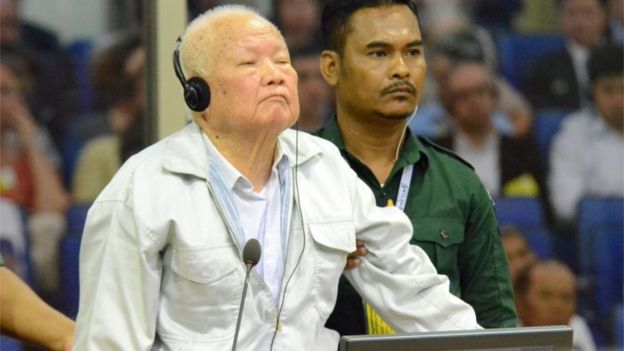

Nuon Chea, 92, was the deputy of regime leader Pol Pot, and Khieu Samphan, 87, was head of state.

They were on trial at the UN-backed tribunal on charges of exterminating Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese.

The guilty verdict is the first official acknowledgement that what the regime did was genocide, as defined under international law.

Up to two million people, most of them ethnic Khmer, are believed to have died under the brief but systematically brutal Khmer Rouge regime between 1975 and 1979.

But the BBC’s South East Asia correspondent Jonathan Head says the larger-scale killings of the Cambodian population do not fit the narrow international definition of genocide, and have been prosecuted instead as crimes against humanity.

The two men – already serving life sentences for crimes against humanity – have again been sentenced to life.

They are two of only three people ever convicted by the tribunal.

Judge Nil Nonn read out the lengthy and much-anticipated ruling to a courtroom in Phnom Penh full of people who suffered under the Khmer Rouge.

They were found guilty of a long list of additional crimes including forced marriages, rape and religious persecution.

But the landmark moment came when Nuon Chea was found guilty of genocide for the attempt to wipe out Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese Cambodians, and Khieu Samphan was found guilty of genocide against the ethnic Vietnamese.

Why is the genocide verdict significant?

The Khmer Rouge’s crimes have long been referred to as the “Cambodian genocide”, but academics and journalists have debated for years as to whether what they did amounts to that crime.

Although Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese died in large numbers, the UN Convention on Genocide speaks of “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group”.

So prosecutors at the tribunal tried to prove that the Khmer Rouge specifically tried to do that to these groups – something experts including Pol Pot biographer Philip Short say they did not.

During the trial, a 1978 speech from Pol Pot was cited in which he said that there was “not one seed” of Vietnamese to be found in Cambodia. And historians say that indeed a community of a few hundred thousand was reduced to zero by deportations or killings.

Apart from being targeted in mass executions, Cham victims have said they were banned from following their religion and forced to eat pork under the regime.

The verdict today may not end the debate completely, but victims groups have long waited for this symbol of justice.

–

Source: BBC