For three days in April 2020, l was unable to sleep, eat or do my work. Why? I was waiting for the results of a COVID-19 test which l had taken to eliminate the possibility that l had contracted the virus after someone close to me had tested positive for the disease.

Mustering the courage to go for the test was not an easy thing to do. And then the waiting started. I was told the results would only be available after three days. My anxiety levels were very high. l had difficulty concentrating and even making simple decisions was a problem. I had difficulty sleeping and when l did fall asleep, l had nightmares.

Unable to cope with these feelings of fear, worry, numbness and frustration, l reached out to a psychologist who explained that what l was going through was ‘normal’. She explained the psychological stress presented by the possibility of having contracted the virus and talked me through my fears. My results came back and I was able to sleep peacefully at night and able to focus on my work.

I am lucky because the majority of the people in Ghana cannot access the kind of psychosocial support and mental health services that l was able to access in real-time to help me deal with the anxiety and fears brought on by the pandemic. More than a year into the pandemic, the constant worry, the fear, the anxiety and the frustrations surrounding access to the COVID-19 vaccine has added to the mental pressures that ordinary citizens are going through.

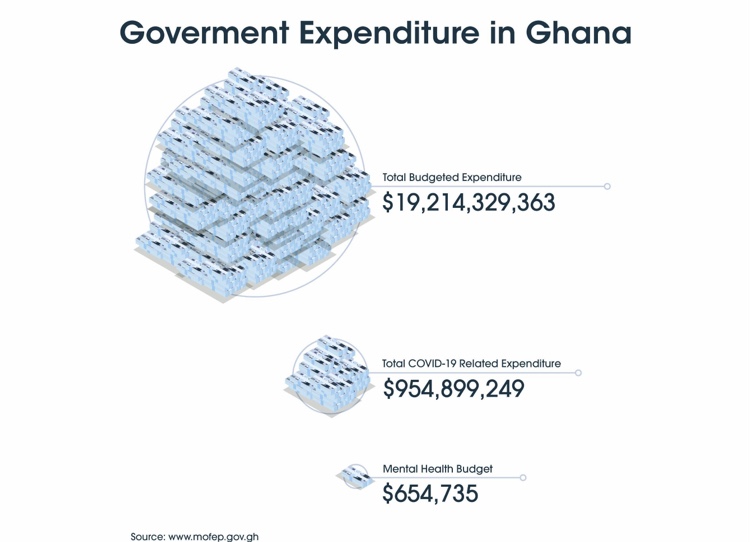

The cost of access to mental health services is beyond the reach of many. Mental health personnel and services are inadequate and have been largely ignored even as the government focuses more on preventing the spread of the virus and managing those who have contracted the disease. Attention to mental health services, even prior to the pandemic, has been woefully inadequate. A mental health policy 2019-2030 document indicates that there are only 25 psychiatrists, 30 clinical psychologists, 7 occupational therapists and 2,500 mental health nurses to cater for a population of 30.8 million Ghanaians.

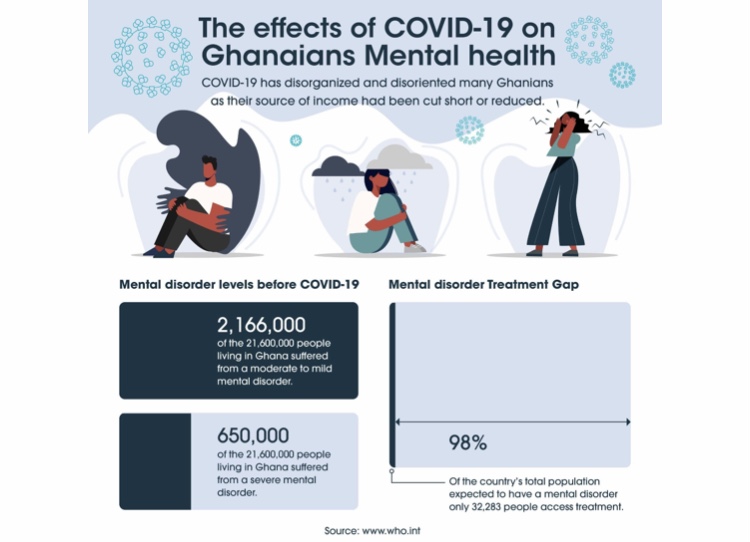

Mental stress has risen as many have lost jobs, have seen their businesses collapse and have been denied the traditional social support they would usually access due to stringent measures introduced by the government to reduce the spread of the disease. Relatives who have lost loved ones to the virus haven’t had the opportunity to bid them a befitting farewell as the bodies are not released to them. All they have are memories of these persons to last them their lifetime.

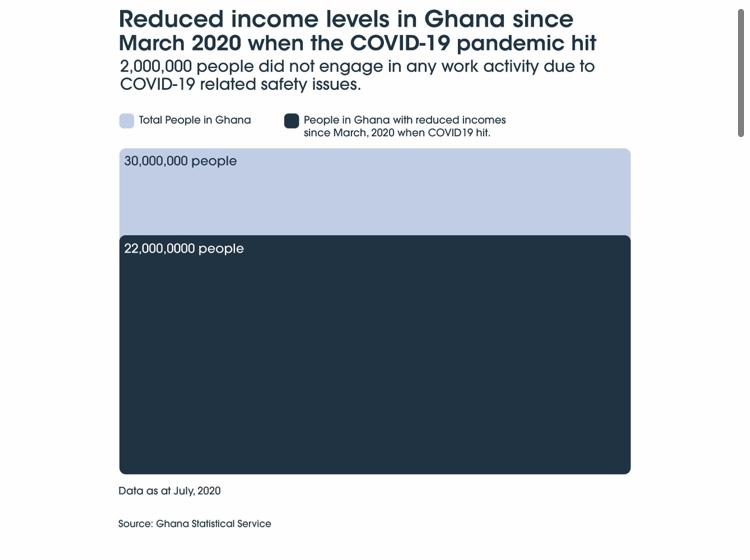

A Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) revealed that the incomes of 22 million Ghanaians out of the over 30 million people in the country has reduced since March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Ghana.

An estimated 2 million people did not engage in any work activity due to COVID-19 related safety issues. The situation has disorganized and disoriented many people as their sources of income have been cut short or reduced.

Aside from exacerbating mental illnesses among patients with a history of mental health conditions, the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 have also impacted those without any previous history.

“In the best of times, mental health is poorly funded. Even more, neglected are the preventative and public health aspects of mental health. An effective response to the mental health impacts of COVID-19 needs to involve the whole of society, with a focus on prevention, integration and coordination across sectors,” Dr. Mohammed Abdulaziz, Head for Disease Control and Prevention, Africa CDC.

The main mental health facility in Ghana, the Accra Psychiatric Hospital relies on donations. The Mental Health Authority (MHA) was established by an Act of Parliament to propose, promote and implement mental health policies and provide culturally appropriate, humane and integrated mental health care throughout Ghana.

The Authority’s Head of Communications, Kwaku Brobbey, acknowledges that the demand for mental health services has increased as the pandemic has continued.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted or, in some cases, halted critical mental health services in 93% of countries worldwide, while the demand for mental health is increasing.

Unlike many economies in the world that were able to provide social safety nets for citizens during and beyond the lockdown, Ghanaians were and have been left with little or no social support, putting them at risk of conditions including anxiety and depression.

The impact of the pandemic on the psychological well-being of the citizens has yet to be measured by the Ghana Health Service. However, anecdotal information suggests that specific sections of the population are showing a higher degree of COVID-19 related psychological distress, something which the United Nations had warned governments about in the early stages of the pandemic and asked states to implement measures to mitigate against these impacts.

The policy brief warned of the additional mental stresses that healthcare workers and first responders as well as the general population were being exposed to as they went about their daily lives which had been disrupted by the pandemic.

The WHO estimates that 650,000 Ghanaians suffer a severe mental disorder and a further 2,166,000 are suffering from moderate to mild mental disorder. Severe mental health disorders are those that impair activities of daily living and sometimes require long-term treatment. Common diagnosis of severe mental illness includes schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Mild mental disorders are those that have limited effect on daily living while moderate mental health illness is where the person has more symptoms that can make their daily life much more difficult than usual.

Access to mental health is fraught with problems. There are only 38 psychiatrists in the country, meaning that the ratio of psychiatrists to the population is 1 psychiatrist for every 800,000 Ghanaians. To meet the shortfall in qualified mental health workers, the Ghana Health Service has trained community nurses from the National Health Insurance Scheme to enable them to diagnose mental illnesses and prescribe medication.

Despite these interventions, few people are aware of the services and the stigma associated with mental illness also means many of them are not seeking the help they may need when they need it.

Dr. Ruth Owusu Antwi, the Head of Psychiatry at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital and the Head of the Psychosocial Support Team for COVID-19 in the Ashanti Region, admitted that more could be done to provide mental health services particularly psychosocial support for citizens in regions outside the Greater Accra and Kumasi.

“There are a lot of mental health experts that were not directly involved in COVID response teams at all. I know of Accra and Kumasi Covid response teams who have done very well in terms of mental health support, and these regions had standing psychosocial support teams and representatives for mental health workers representing stakeholders meeting when it came to fighting the pandemic. But many of the remaining regions and districts have not involved mental health workers and so in that sense I think we have not done very well. I however applaud Greater Accra and Ashanti Regions for what they have been doing,” she says.

She admitted that more could be done to support citizens who have had to cope with mental health issues arising from the pandemic.

“Psychosocial support plays a vital role in the fight against this pandemic. In our part of the world, when people lose their loved ones, we have to pay our last respects. When funerals and other similar social gatherings are suspended or are curtailed and you are not able to pay your last respects, this can result in mental health problems. There is no closure, anxiety and depression worsen. Mental health should have been part of the management of the pandemic, but we didn’t see that largely in how we dealt with this issue in this country,” she says.

Technology to the rescue?

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, patients seeking mental health consultations were required to visit the hospital and book appointments at the clinics if they needed it. But the pandemic has forced mental health service providers to rethink how to reach patients and enable them to keep their appointments. Even though in-person consultations are still happening, attention has shifted to expanding access using e-health methods as it is now easier and quicker to book a virtual session than pursue the in-person sessions.

The Accra Psychiatric hospital as part of the mental health awareness month for the month of October introduced a free call-in for mental health counselling.

Why can’t it be sustained?

I put this question to a member of the Public Relations team of the hospital, Francisca Ntow.

She says that “the long-term goal for the Accra Psychiatric hospital is actually to run a telemedicine unit looking at the challenges or limitations Covid-19 has brought”.

The theme for this year’s theme for World Mental Health Day was mental health in an unequal world.

The call-in service is one way the hospital is trying to bridge the gap in access to mental health services.

“WHO studies show that for most low-income developing countries like Ghana, the treatment gap is between 75-95 per cent. It’s worse in Ghana where the treatment gap is around 98 per cent. This means that there are a lot of people who are unable to access mental health services,” says Ntow.

The Head of Communication of the Mental Health Authority, Mr. Kwaku Asenso Brobbey says the mental health call centre was established in response to the increase in the demand for services.

“What we initially had was a suicide helpline and there were a few numbers available for people who felt suicidal. But with the pandemic, we have had to increase the number of helplines because there were a lot of people who were undergoing psychological distress and needed to talk to the professionals”

They have counselled many who are distressed and going through depression and the call centre runs 24 hours. While this is a great initiative by the authorities to help people in distress, there is so much more that can be done to publicize the numbers so that people who need help can easily access them.

The Authority can liaise with media houses and other interested groups to push for help to reach the masses. This is because many who have challenges won’t have the luxury of time to go online to look for numbers to seek assistance.

Just like there’s an emergency line (112) that you call and can easily be directed to either the ambulance, fire service or the police, a short code (USSD) can be generated to make things easier.

In Ghana, misinformation regarding COVID-19 was a stressor for anxiety, fear, and confusion among citizens, which was why Atsu Latey and his team at MindIT Ghana created the Telegram chatbot to address this issue.

For those who don’t own smartphones and have no internet access, there is a tool-free short code (USSD) which they can use to access updated information about the pandemic in Ghana, tips on how to keep safe and emergency numbers that they need to call if they need any information on the pandemic.

Suggestions have been made to expand the COVID-19 helplines that the government has set up to incorporate the delivery of brief psychological interventions to the public. However, there are concerns about how to standardize online mental health practices for web-based counselling and therapy sessions tools.

Suicide/distress hotlines have also been providing callers with suicide intervention services as well as mental health first aid to callers; all of whom are subsequently referred to appropriate quarters for specialized care. Providing consultations through digital platforms or by phone has had varying degrees of success.

The following are some of the helplines that people can call to get assistance.

Community-based self-help groups are another way of providing mental health services to the population especially those in the rural areas. For example, in the Upper East Region of Northern Ghana where people are not able to access mental health services, afford medications and endure discrimination and stigma, self-help groups have been providing mutual support.

These self-groups are part of a programme by the Presbyterian Community Based rehabilitation program based in Sandema. These groups established in 2008 have been an important source of support for those with psychosocial disabilities, especially during the pandemic.

The 23 self-help groups in the region each have about 100 members. They conduct advocacy campaigns to help reduce stigma and discrimination against people with psychosocial disabilities, and also disburse $260 (840 Ghana Cedis) per year per client for medication.

But even these kinds of community-based psychosocial support activities have been severely impacted as in-person meetings have decreased due to fear of infection especially among older people suffering from mental health problems. The stigma surrounding this also means few people will go out of their way to access these services even if they were available.

“The government must prioritize mental health and give the various facilities, agencies and personnel the support they need to function effectively. Failure to do this will make the situation worse. Our mental health is as important as our physical health. Ignoring one for the sake of the other is untenable,” says Peter Yaro, the Executive Director of Basic Needs, an NGO trying to meet the mental health service gaps.

This article was produced by the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).