There are many theories postulated for ensuring a technologically transformed and innovative economy. One of such theories is, find winners and invest in them.

With this theory, the government would have to find that one champion of a technology agenda and do big procurement with that champion to enable the champion scale and influence the economy. The flaw in this theory is, many at times it is challenging for a government to choose based on merit, unbiased process, or data-driven insight. The other flaw is, it becomes a conduit for corruption.

In this theory lies strict accountability and quality assurance issues. This theory is anti-innovation and counter-productive to technology transformation. Apart from the nation not developing compelling variants of viable solutions, the champion who has scaled may suffer from his success. Why? The champion would have little incentive to push the frontiers of his or her core offerings. Best case is, he or she would become a potentially financially sound monopoly, diversify into different ventures leveraging his wealth; however, the champion’s downfall would come from a subculture of lack of accountability, lack of focus, misplaced experimentation and the zero-need for critical thinking. More often you would find that such champions would not spend the time to build the level of operational rigour that would support the quantum-leap in scale.

In the past 10 years, we have seen an example in RLG. In recent years, we have seen less of the RLG company than we used to see some few years ago. The often-unexplored dynamic in taking the follow-and-scale-the-champion path is the powerful catalycism of deepening competition in product spaces and service ecosystems.

With the scale-the-champion model comes what I term the Transformation Introversion Syndrome (TIS). The country virtually would not be able to scale or export such innovation, because the absence of the discipline and operational rigour in running such entities make it difficult to export such innovation to influence cross-border or global trade. Consequently, it becomes daunting to bring foreign exchange to our nation while on the contrary yet ideal side, we know countries have often exported their innovation to influence global economy and shape global trends. May we be the scale-the-champion model becomes more compelling when we have a benevolent and ethical champion who does not sit on their laurels. With foresight, he or she is able to build world-class solutions and subcultures that provide very tangible benefits to the society.

The enclavement theory

The second theory around creating technology transformations is what I term enclavement. In enclavement, proponents believe that government should invest in one champion enclave, mostly a physical location where technology and innovation firms are brought together in closely knit physical and ideological proximity.

The belief is that when for example investment are done in such enclaves they would become shining role models for other communities within the country.

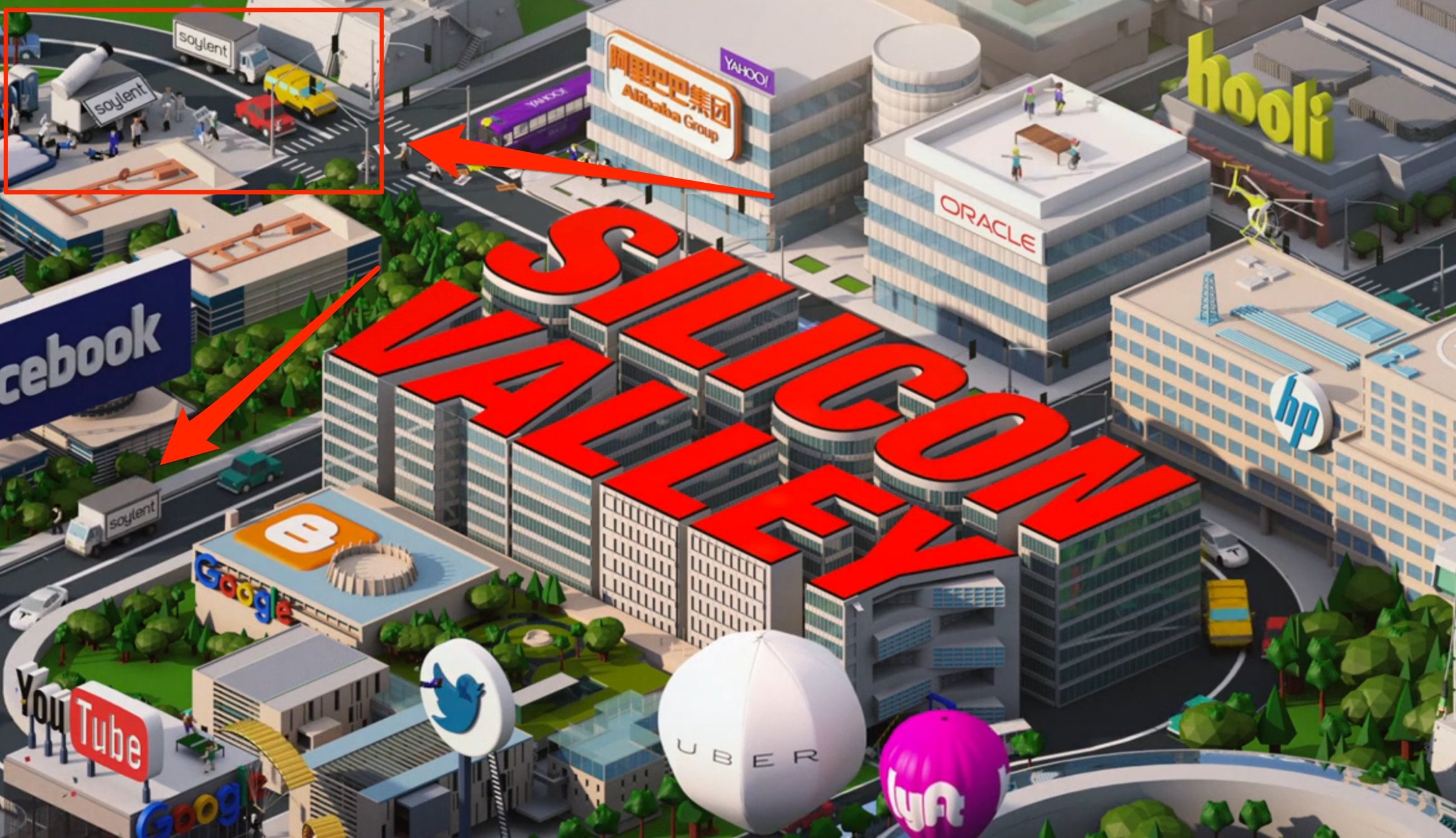

A simple case would be to mimic Silicon Valley by establishing a tech enclave in a suitable location in Ghana. The optimistic assumption is that actors of that technology transformation, mostly empowered by government, would find new markets to conquer within or outside the country as their enclave grows and becomes too concentrated and pose little challenge to warrant their entrepreneurial attention.

The other proposed advantage is, such enclaves may create Positive Envy (PE) in other vicinities or geographical hotspots. This Positive Envy, it is suggested, would generate a positive-mimicking of the trend by new vicinities. More or less, the thinking is, in an ideal situation there would be in a nuclear bomb fashion, an explosion of mushroom cloud burning an innovation subculture that would drizzle across different vicinities in the country. Silicon Valley is a benchmarkable example of a well-played-out enclavement model.

Enclavement is a great way to build infectious innovation subcultures that can self-scale. However, the downside of enclavement if pursued in Ghana’s context may be cronyism, nepotism, and partisan politicking especially if such innovation enclaves have enormous government influence. If the enclaves are orchestrated and hatched by a government, they tend to live on government benevolence and life support. Such enclaves also have shorter timelines mostly tied to the terms of the governments who set them up. The enclaves make much sense if they are backed by powerful private sector entities who have the financial muscle, commitment and subculture to drive it.

Tech Hubs

Technology and innovation hubs have gained prominence in the evolution of Ghana’s technology and innovation subculture in the last decade. A technology and innovation hub is a space where technologists, computer scientists, hackers, web developers, programmers and people interested in technology gather to network, learn, share programs, and designs to bring their ideas to fruition. They provide co-working environments that can offer a variety of services like community building, pre-incubation, incubation, acceleration and maker spaces.

The great side of such hubs is the sense of community it generates for individuals to get inspired, dream, and nurture the inkling to execute their dreams. Innovation hubs are useful to the extent that they can be delivered within casual and unstructured settings. They even get more forbearance if large corporations buy into such communities and offer resources to support the members and the agendas of such hubs. In Ghana, we have not less than 10 hubs, and there is a need to create more.

The challenge that stares at such hubs are the evident lack of diversity especially of women who actively participate in such hubs compared to the male counterparts. Also, the hubs do not get the desired support needed to scale and become competitive hubs that can deliver the innovations we need to find solutions to crucial problems facing our people.

Often, beyond piecemeal photo ops activities and events, we don’t find corporations actively collaborating and supporting such hubs as they should. Tech hubs also face critical infrastructure challenges such as poor yet expensive internet, unreliable energy supply and the prevalent lack of enabling social sentiment that will derive a resonating narrative that can ensure their success.

In dealing with the challenges that confront the nation in our technology space, governments historically have been busy at work. Over the years, we have seen a blend of different initiatives by various governments such as the National Science and Technology Policy, National Information Communication and Technology Policy, the Accra Digital Centre plus a host of several entrepreneurial events and shows on radio and TV. In the 2017 Budget, the government sought to build an entrepreneurial nation using the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Plan (NEIP) as the primary vehicle.

The stated objective was to provide an integrated, support for early stage (startups and small) businesses, focusing on the provision of business development services, business incubators, and funding for youth-owned businesses. As part of Ghana’s 60-year anniversary celebrations, the Jubilee Innovation Challenge (JIC) was launched in February 2017, to develop innovative apps that would help shape businesses in Ghana. If I may ask, what were the outcomes of this competition? In May 2018, Daily Graphic reported that the government has started a GHC 60 million fund for startups under a presidential pitch competition programme. The extent to which these initiatives have gone or will go to help our digital agenda, can only be measured by the evidence we see now? Do the evidence manifested over the period tell a laudable story on the outcomes of our past and existing digital strategy as a nation?

Stay tuned for edition 3.

–

By: Derrydean Dadzie

The writer is a Technology Entrepreneur, Fintech Expert, Digital Policy Advisor and Digital Transformation Consultant.

derry@derrydean.blog | twitter: @legenderrydean | www.derrydean.blog